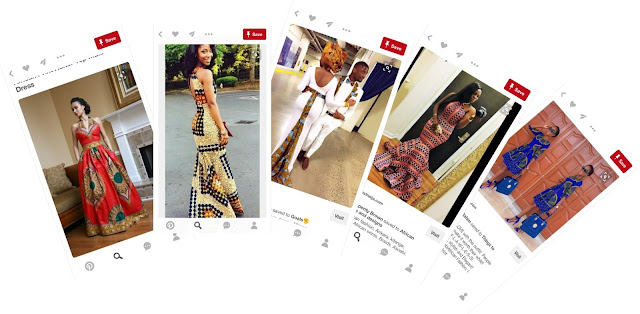

I was scrolling through Pinterest while sitting in a salon chair on a Wednesday trying to find the perfect hairstyle for my friend’s upcoming Texas wedding. It’s unheard of to move to a new city and discover a salon home on the first try, but thanks to the help of Yelp, I found a professionally ran salon with multiple stylists who can do my natural hair. I remember giving the heads up, like I do every time I make an appointment at a new salon over the phone, that I need a stylist with experience with black hair. When I lived in Germany, the stylists gathered around in shock to hear me tell the challenges of getting a simple blow-out at just any American salon because competency with textured hair is a novelty that most salons do not have. Even when this salon confirmed they could, I was still skeptical. I’d heard that claim before. But with multiple visits with multiple stylists, they have never disappointed. Here, I don’t need a separate salon for braids, extensions, curls, processed, cutting, or my straight hair, I have it all in one here. This just doesn’t happen. In spite of Back Bay prices, the search is over.

|

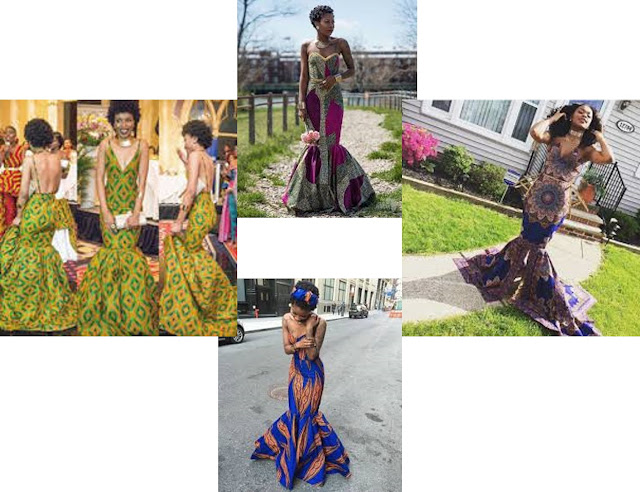

| I need these gowns in my closet! |

When a gorgeous formal, European-cut gown in West African fabric popped up among the different natural hair options, my stylist and I both gasp in delight. Perhaps I should track down a dress like that to wear to the

wedding. That would be a show-stopper for sure.

|

| Can you believe the girl to the right was told by her teacher than African dresses were too tacky for prom!? |

“You know, there are Africans that don’t like us wearing their fabric,” I told my hairdresser, an immigrant from Haiti. I recalled a blog of a British Nigerian woman accusing African-Americans of cultural appropriation of Africans. My hairdresser paused in near disgust before responding in her sweet, girlie accent, “Well, that is their opinion. We can have ours.”

A discussion continued between me, her, and a Brazilian hairstylist who also does a great job with my hair but most would not visually identify as being part of the African diaspora. Who are “they” to exclude “us” from “our” heritage, we all agreed.

After my hairdresser had me looking like a chic it-girl, I attended a monthly Black Young Professionals mixer. This is the one time a month that I get to interact with other black people in Boston. In five months the only times that I’ve actually seen other black people is if I intentionally coordinate to meet up with a friend I met via social media (we had too many friends in common not to meet) or take an intentional cruise through Roxbury. I spent two years in SoCal with minimal black interaction. Outside of the hair salon or a deliberate visit to Englewood, I went two years without face-to-face interaction with black peers. I committed to not going another two.

I drop my car off with the parking garage attendant— a man with an accent. I ask where he hailed. “Africa — the original land,” he responds with a smile.

In Boston, there’s a significant Caribbean and African population. Out of curiosity, I asked him to specify where in Africa. He indicated Ethiopia.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

I wrestled with this. I always wrestle with this. What answer should I provide? Often I claim to be from the Air Force which explains my nomadic lifestyle. Most often I proudly claim Kentucky with Alabama roots even though I wasn’t born in either. I sometimes claim “The South” as a whole. But in this instance, I wondered if he was asking me to identify an African country, and I can’t. He sees the bewilderment on my face.

“You are also from Africa” he answers for me. He claimed me as part of him. And I was content.

Inside, a spread of young professionals with a beautiful array of skin hues still in their work clothes filled the space. I join a circle of women and make small talk about our careers, the upcoming cuffing season, and travel. You’ve got Harvard engineering graduate students, STEM professionals, accountants, classically trained musicians, and performers–all networking, discussing current events, and planning bougie black people activities like apple picking, weekends at the cape, going away parties for week-long vacations in Thailand, and upcoming NSBE galas. In this space, no one needs to ask what NSBE is, regardless of their discipline. The mixer is a refreshing space free of micro-aggressions, having our hair touched, being petted, conversation topic avoidance, explanations of who we are, and all the various other forms of small talk often used to “other” us from the in-group. It’s a place where all the young women have melodic names printed on their name tags. My own doesn’t stand out as unique, and people confidently pronounce it correctly on the first try.

A guy joins the circle and takes a look at our name tags and asks if we’re all from Africa. Everyone except me nods their head. I would never have guessed, even after talking with them for a half-hour. Most of the girls initially identified different hometowns but when explicitly asked if they were African, they each surprised me when they dropped a different country.

| This dude is one of my favorite people to talk to. |

Later, in the evening I get asked where I’m from, and I proudly proclaim Kentucky.

That response elicits blank stares before the guy responds, “Ok, so regular black.”

Wait, What? There is nothing regular about a Kentuckian I think to myself. I’d never been labeled such a thing as “regular.” I understand the distinction he is making. Since then, “regular black” and “just black” has become the Boston norm in identifying Black Americans who could not identify what country they come from. The only other time I had heard of “regular black” was when I asked a friend if he considered himself light skin. He responded, “No. Regular black.” At the time, I took it as a color

reference rather than a cultural reference. I also thought it was funny.

In the span of one evening, I had been called “African,” “Just Black,” a member of the “African diaspora,” “Regular black,” and called “of African descent but not African.”

So naturally, that evening, along with the blog opinion by the British Nigerian rejecting my American African-ness, got me reflecting on associations and identity. At what point did we stop being African? Is African-ness something that can be lost, stolen, or stopped?

In 1787, Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and others founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Philadelphia after white Methodists physically pulled the black Christians up from their praying knees. Even though the founders were born in Delaware Colony, they still identified as Africans. At the time of the Civil War, American colonies hosted 10 generations (over 200 years) of people born in America but originating from Africa, and yet they were still called Africans. The Articles of Secession from both Georgia and Texas discussed the servitude of Africans even though the document had been 53 years since the last legal arrival of imported Africans.

In 1868 Africans were granted citizenship by the 14th amendment but

without the benefits of citizenship and not the identification of Americans. This was the time frame that Africans shifted from being logged as taxable property items to being counted on the U.S. census. Mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon were labels forced upon black people in relation to their relative whiteness before utilizing “colored” as an all-encompassing catch-all (although I had classmates in Kentucky still using all of these dated terms in the 2000s).

Ida B. Wells (1861-1931) used the term Negro before switching to Afro-America as a conscious effort to connect to her ancestors. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) wavered in the usage of Negro and Afro-American. MLK, Jr used the term “Negro,” and Malcolm X used, “so-called Negro” during the 1960s. It wasn’t until 2000 that the U.S. Census had “African-American” as an option; however, Jesse Jackson highly encouraged the use of the term back in 1988. Then there’s the widely popular, more inclusive “Black” which includes everyone of a certain skin hue range (although there are those with the same skin color who identify as brown) and the more segmented “Black-American.”

Perhaps more beneficial to the quest to understand when we stopped being African, is to discover why we ended being African.

In the past, I’ve identified as Black-American to make a distinction from African-Americans who had direct ties to a specific country in Africa. My grandmother, who has navigated life as a white-presenting black woman always scratches out the “African” in “African-American” when identifying her ethnicity. She is adamant about identifying as just as American as anyone else…no qualifier needed. Sometimes, people at doctor’s offices don’t even ask and mark her as white.

I have to go abroad to be an American. Rarely am I treated as “just American” while I’m in America. In subtle ways, like Almay calling Carrie Underwood’s look the, “true spirit of American beauty” to the not so subtle demands to, “go back to Africa” when someone disagrees with me, or a US representative warning the American president to, “Watch out, Real America is coming,” I am too often reminded I am an outsider in the land I claim.

I’m realizing now that my grandmother was identifying as “just American” and me recognizing as Black-American erases our connection to Africa. And perhaps that’s by colonial design. I think it may be instinctual to disassociate with Africa because Colonizers crafted a negative perception of Africa. For those who have not visited, Africa brings the connotation of poverty, disease, “jungle savages, cannibals, and nothing civilized.”

|

| We both identify as black, but we aren’t always recognized by others the same way. |

Likewise, for first-generation Africans and Caribbeans, Black-Americana holds the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow characterizations of blackness and various other unsafe, negative stereotypes. And thus, we disassociate from each other. Perhaps Black Americans claim the American label tighter in an unconscious effort to prove our American identity…something denied to us for centuries. Maybe we more closely identify with America since we’ve never lived in or perhaps even visited Africa.

Nevertheless, when a Black American and Black African travel the globe, no one sees nationality. Everyone sees the continent. I cannot count the times Europeans have told me I look like the people from some African country they visited. Or just assumed I spoke French. Or Spanish. I’ve been pulled aside in international airports and asked if I’m coming from Kenya. Like, why, of all the countries in the world would they ask me, of all people, if I’m coming from Kenya? In America, Africans are regarded as the same as Black Americans.

Going back to Zipporah Gene’s original blog post, she states, “I’m not trying to start a war, but I would just like you all to realize the hypocrisy of seeing someone wearing a Fulani septum ring, rocking a djellaba, painted with Yoruba-like tribal marks, all the while claiming that this is meant to be respectful. It’s a hodgepodge, a juxtaposition, a right mess of regional, ethnic and cultural customs and it screams ignorance and cultural insensitivity.”

Going back to Zipporah Gene’s original blog post, she states, “I’m not trying to start a war, but I would just like you all to realize the hypocrisy of seeing someone wearing a Fulani septum ring, rocking a djellaba, painted with Yoruba-like tribal marks, all the while claiming that this is meant to be respectful. It’s a hodgepodge, a juxtaposition, a right mess of regional, ethnic and cultural customs and it screams ignorance and cultural insensitivity.”

This response does a pretty solid job at explaining why it is not possible for African Americans to appropriate African culture. So does this response. So I’ll refrain from repeating the same sentiments but offer my perspective.

After many cries of foul play, Zipporah Gene wrote a follow-up blog post ironically titled No One Can Take My Africanness Away. In it she states,

“What people fail to understand is that unlike those from the diaspora, I can never look at the elegant wrappers/kente of Ghana and decide that I prefer their styles to my tribe and wear it. It is a near unspoken rule. We have our lines, and we don’t cross them.”

But what the author fails to understand, the thing about being part of the African Diaspora is. Those lines have been crossed. That is precisely who we are. We are a mix of Cameroon, Ghana, Angola, Senegal, Nigeria and more.

We are all of Western Africa rolled into one. Gene may only identify as Nigerian. It may very well be inappropriate for her to mix elements of cultures. But American-Africans are that hodgepodge, juxtaposition, and “right mess of regional, ethnic and cultural” identity. Colonialism and imperialism dislocated and built arbitrary borders where there once were none. For her not to recognize that screams of ignorance and cultural insensitivity right back.

Further, she identifies as both British and Nigerian and perhaps she’s not altogether familiar with Black American history. In what sounds like African elitism run amuck, she states, “Unlike a lot of people from the diaspora, I do know my tribe.”

I contend that American Africans have developed a new tribe out of many. Every tribe and every nation in Africa is different. There is not one thing that unifies Africans but Africa itself. If 4 million Yoruba people migrated to Norway, their attire, foods, and activities would change to adapt to the new environment alone. To survive, they will take on the language of their new land. Norwegian history will not magically become their own. They will not magically turn into Norwegians although their citizenship may say so, they will still be ethnic, native Yorubas, doing the things Africans would do to adapt to the Norwegian climate. Likewise, American Africans live the way “African-Africans” would live had they been kidnapped and treated like livestock for half a millennium. The culture, ethnicity, and identity fused and evolved but never dissipated.

I cannot help but notice that the author, Zipporah Gene, bears the same name as the wife of the Biblical figure, Moses. Moses, although adopted, given an Egyptian name, and raised in Egyptian culture (he wasn’t even circumcised and neither were his sons), never stopped being an Israelite. When he learned of his heritage, he felt an immediate kindred spirit when he saw the mistreatment of an enslaved Israelite. Moses didn’t learn all the cultural aspects of his true identity overnight. He had to grow and learn and fortunately he had people willing to show him the way. The Israelites, when they lost their way by abandoning their customs and worshiping the false gods of Egypt, never stopped being Israelites. Your location and practices may shape your experiences, but it doesn’t define who you are.

The British colonization of Africa left a similar inheritance of displacement that African-Americans experienced. The Brits relocated Sudan’s Nubian population to Kenya. When the British pulled out of Africa, they granted British citizenship to the Chinese they cajoled into fighting in their military but the Nubians who did the same lost citizenship to both Sudan and Kenya. They became stateless—belonging to no African country. This was the state of most Africans in America until late last century. It just so happened, that Nubians were dislocated within the continent of Africa that they uncontestably maintained their African-ness even without citizenship of an African nation. The examples of dislocated and relocated people who adapt yet keep their identity are endless.

Being from Kentucky, I am conscientiously southern. It is an identity that I defend. Perhaps because New Englanders, although never visiting the state have always assumed it was mid-West. Perhaps because some Southerners question belonging to the group I am hyper-aware of claiming southern as my identity.

I ponder if a Southerner moves to Wisconsin, and maintains southernisms, can that person still claim the south? If that same individual’s child grows up in the mid-west and learns ice-fishing, eats cheese curds, knows how to drive in the snow, doesn’t get gussied up to attend football games, can’t identify a grit or worse — puts sugar in them, is that descendant still a Southerner? Southernness is more than a geographical designation. It’s deeper than the superficial eating of grits. So is African-ness. Perhaps in claiming Africa, I’m continuing the 400-year-old resistance to having my identity taken away.

No doubt, we do not have to all agree on how to identify ourselves. Identities are often fluid and based on relation to others (i.e., I never needed a term for “Just black” until I was around a diversity of other black people). Even people within the same family identify in different ways (my mom, her sister, and their mom have different last names but all family) so expecting 41 million people self-identify the same way is fruitless. It is pivotal to recognize that race, nationality, and ethnicity are not mutually exclusive. Instead of identifying as this or that, consider identifying as this and that. It is possible to be Black, American, an Islander, and African. Recognizing alternative options on what fits you best be it Black-American, African-American, American African, or American And African may be beneficial and most accurate.

One of my last courses for my Master’s in International Relations required us to define our own culture. At the time I just didn’t have the resources, perspective, or time between deadlines to give the assignment justice. The task was more fascinating than I realized at the time and a fun conversation to have (with the right people). Perhaps I’ll devote more time to research and explore this later.